China’s REM Squeeze make Indian Autos vulnerable

The squeeze exemplifies how the US-China conflicts impacts India, potentially reshaping its EV-focused auto industry; also foretells that China may leverage supply shortages for hard bargains

The automotive industry faces a looming crisis as China’s rare earth magnet (REM) embargo threatens to disrupt global supply chains, evoking memories of the post-COVID semiconductor shortage. While the earlier crisis stemmed from natural disasters and saw a collaborative global response, the current REM shortage is driven by geopolitical tensions and tariff disputes between the U.S. and China. This strategic weaponization of REM supplies, with China controlling 90% of the global market, places countries like India in a precarious position, facing collateral damage with no quick resolution in sight. The automotive, electronics, and electrical sectors are particularly vulnerable, with electric vehicles (EVs) and electric two-wheelers (e-2Ws) at the highest risk due to their reliance on neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets.

The Scale of the Challenge

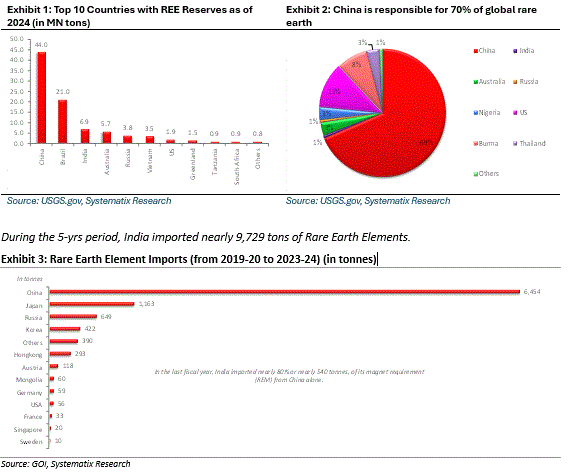

Rare earth magnets, though constituting less than 5% of the total cost of electric passenger vehicles (e-PVs) and e-2Ws, are critical for EV motors and other components. India, which imports 80% of its REM requirements from China, faces significant supply chain risks. Channel checks reveal that auto manufacturers currently hold only 2–4 weeks of magnet inventory; Maruti Suzuki India Limited (MSIL) has stock that would last till end of July 2025, and Tata Motors, which reports comfort for the next few months. However, if Chinese supplies remain restricted, production delays are inevitable, particularly for battery electric vehicle (BEV) programs. Industry estimates suggest a minimum of six months to resume normal supply chains, with ongoing U.S.-China negotiations offering no clear timeline for resolution.

The impact on pricing is already evident. Channel checks predict 5–8% price hikes for EVs and e-2Ws, translating to an additional Rs. 8,000–12,000 for an electric scooter priced at Rs. 1.5 lakh. This could exacerbate existing challenges in the Indian passenger vehicle (PV) market, where inventory levels have risen to 52–53 days of sales, compared to the typical 30–35 days, due to slowing domestic demand. While elevated inventories provide a temporary buffer, they also weaken original equipment manufacturers’ (OEMs) pricing power, forcing deeper dealer discounts. A prolonged magnet shortage could allow dealers to reduce discounts, but OEMs are unlikely to see significant benefits until excess inventory clears.

India’s Vulnerability and Strategic Response

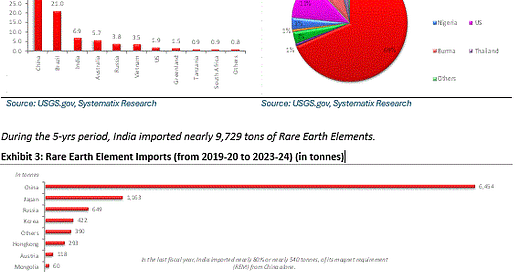

India’s reliance on Chinese REMs highlights its vulnerability, particularly as its 6.9 million tonnes of rare earth element (REE) reserves are primarily light REEs, unsuitable for industrial-grade magnets. The Indian government is taking proactive steps to address this dependency, promoting local production through initiatives led by organizations like the Indian Rare Earths Limited (IREL) and the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC). These efforts aim to tap domestic reserves and develop processing capabilities for high-grade magnets. However, experts estimate that building a robust domestic supply chain could take 7–10 years due to challenges in mining, technology development, and OEM qualification. For instance, Epsilon Carbon, a component manufacturer, notes that scaling up technology and securing OEM approvals could take 4–5 years, with an additional two years to build production facilities.

To mitigate near-term risks, the government is exploring production-linked incentives (PLIs) and public-private partnerships to boost indigenous magnet production. Companies like IREL, Entellus, and Midwest Advance Material are engaging with policymakers to develop local capabilities, but timelines for commercial production remain unclear. Recycling offers another potential solution. Attero, an e-waste recycling company, is investing INR 1,000 million to scale its rare earth recycling capacity from 300 tons to 30,000 tons within 1–2 years. Globally, Ford’s 2025 strategy includes recycling EV magnets to recover 90% of neodymium, signaling a broader industry shift toward sustainable alternatives.

Alternative Supply Sources and Industry Impact

Beyond China, potential REM sources include Australia, Latin America, Vietnam, and Indonesia, though these remain largely untapped. Developing these supply chains will require significant investment and time, leaving automakers exposed in the interim. The Indian automotive market, where EVs account for only 7% of sales (94% of which are e-2Ws and e-3Ws), is somewhat cushioned by its reliance on internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, which dominate 93% of the market. However, even ICE vehicles depend on magnets for components like motors, power steering, and wipers, meaning prolonged shortages could force manufacturers to divert limited inventories to ICE models, further delaying EV production.

The impact varies across manufacturers. Premium PV and EV players like Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M), Hyundai, and Tata Motors face higher risks due to their focus on EV segments, while Maruti Suzuki remains less exposed, benefiting from its dominance in low- and mid-end ICE segments. Among two-wheeler manufacturers, EV-focused companies like Ola and Ather are under pressure due to their reliance on NdFeB magnets, whereas Honda, Hero MotoCorp (1.9% EV share), and TVS Motor (8.9% EV share) are less affected. Bajaj Auto, with a 14.9% EV share, faces moderate exposure, while tractor manufacturers like Escorts and M&M are largely insulated due to minimal REM use.

What Lies Ahead?

The REM embargo could reshape India’s automotive landscape. JATO Dynamics India predicts manufacturing delays of 2–6 months if the situation persists, with ripple effects on pricing and market dynamics. Potential easing of China’s embargo, possibly tied to greater market access for Chinese EV OEMs in India, could intensify competition in the premium PV and EV segments, challenging domestic players. In the long term, India’s push for self-reliance through domestic mining, recycling, and alternative sourcing is promising but requires significant risk capital and time. For now, the industry braces for a period of uncertainty, with EVs bearing the brunt of this supply chain déjà vu.